According to the report, it is technically possible and absolutely necessary to achieve the 1.5 degree goal. Actions must be taken especially at the level of mobility, energy and agriculture, at European and national level.

In addition, Luxembourg's position on CO2 emission standards for cars and vans - on the agenda of the Environment Council of 9 October 2018 - was presented.

1. Where are we?

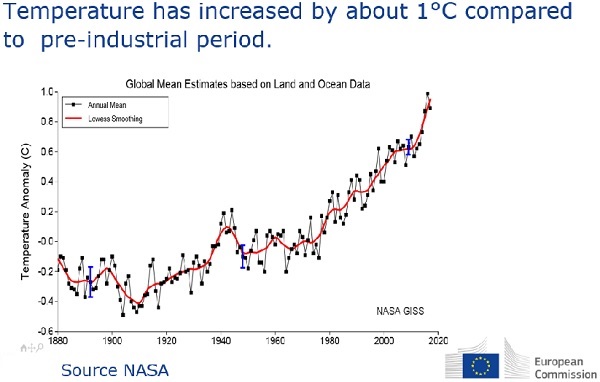

• If the current warming rate of about 0.2 °C per decade continues, human-induced warming will exceed 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052.

• Warming from anthropogenic emissions will persist for centuries to millennia and will continue to cause further long-term changes in the climate system, such as sea level rise, but these past emissions alone are unlikely to cause global warming of 1.5°C.

• In model pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C (2 °C) CO2 emissions decline by about 45 % (20 %) from 2010 levels by 2030 reaching net zero around 2050 (2075). Non-CO2 emissions show deep reductions that are similar in 1.5 °C and 2 °C pathways.

• Fulfilling the current pledges under the Paris Agreement () will not be sufficient to limit global warming to 1.5°C even if supplemented by very challenging increases in the scale and ambition of mitigation after 2030. The greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the current NDCs of about 50-58 Gt CO2eq in 2030 would be about twice as high as in 1.5°C pathways .

• The remaining carbon budget for a one-in-two chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C is about 770 Gt CO2 for a one-in-two chance and 570 Gt CO2 for a two-in-three chance. These estimates are larger than those estimated in the AR5 and they are subject to an uncertainty that is of a similar size as the budget estimates themselves. Further updates can be expected as research progresses, but with current emissions of about 42 Gt CO2 per year the budget for 1.5°C would be depleted in less than two decades.

2. What are the benefits from limiting warming to 1.5°C?

• Tipping could be triggered around 1.5°C to 2°C of global warming. This includes risk of irreversible loss of many ecosystems or ice sheet instabilities that could result in multi-meter rise in sea level over hundreds to thousands of years.

• Risks are significantly lower for natural and human systems for a global warming of 1.5°C than for 2°C, including the frequency and intensity of extremes, impacts on terrestrial and marine biodiversity, ecosystems and their services, health, livelihoods, food and water supply, human security, infrastructure, and economic growth.

• However, limits to adaptation and associated losses exist even for 1.5°C warming with site-specific implications for vulnerable regions and populations. Some impacts will continue beyond 2100, like sea level rise, or be irreversible, even if we limit warming to 1.5°C.

3. How can we limit global warming to 1.5°C?

• All 1.5°C-compatible reduction pathways require a radical reduction in CO2 emissions, with net-zero CO2 emissions around the middle of the century and concurrent deep reductions in emissions of non-CO2-forcers, particularly methane and black carbon. 1.5°C-pathways are characterized by far-reaching transitions in energy, land, urbane (transport and building) and industrial systems-. Low energy demand, low material consumption and low GHG-intensive food consumption facilitate limiting warming to as close as possible to 1.5°C. Limiting global warming to 1.5°C would require timely enhanced action by countries and non-state actors and unprecedented system transitions , in terms of scale, but not of speed, during the coming one to two decades

• If temperatures rise beyond 1.5°C, CO2 would need to be removed from the atmosphere, later in the century, to return the temperature back to 1.5°C following an overshoot. Limitations of the speed, scale and social acceptability, determine the ability to return back to 1.5°C-. The higher the temperature overshoot (i.e., larger exceedance of the carbon budget), the greater the reliance on negative emissions technologies, unproven to work at large scale.

• All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5°C contain the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5°C following a peak. CDR deployment of several hundreds of GtCO2 is subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints. Significant near-term emissions reductions and measures to lower energy and land demand can limit CDR deployment to a few hundred GtCO2 without reliance on bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS).

4. How can we limit climate change to 1.5°C and foster sustainable development?

• Climate-resilient development pathways (CRDPs) are pathways that aim at limiting warming to 1.5°C while adapting to its consequences and simultaneously achieve sustainable development. CDRPs require a massive boost of near term mitigation action to avoid impacts due to further warming, in particular temperature overshoot and associated risks, and to decrease the dependence on CDR-technologies. Such pathways would entail lower transitional challenges after 2030 due to a smaller pace and magnitude of change in the long term. CDRPs emphasize low energy demand, low material consumption, and low emission-intensive food consumption. .

• International cooperation, strengthening the institutional capacities of national, subnational and local actors from civil society, the private sector, , local communities and indigenous peoples, as well as the consideration of poverty reduction and equity are central to CRDPs.