In-work at-risk-of-poverty rate in Europe in 2024;

Credit: Eurostat, 2025

In-work at-risk-of-poverty rate in Europe in 2024;

Credit: Eurostat, 2025

Luxembourg often ranks among the world's wealthiest nations, boasting the highest GDP per capita and the highest average salary in the European Union (EU) and yet, behind this image of prosperity lies a less comfortable reality: the country also has the highest rate of "working poor" in the EU.

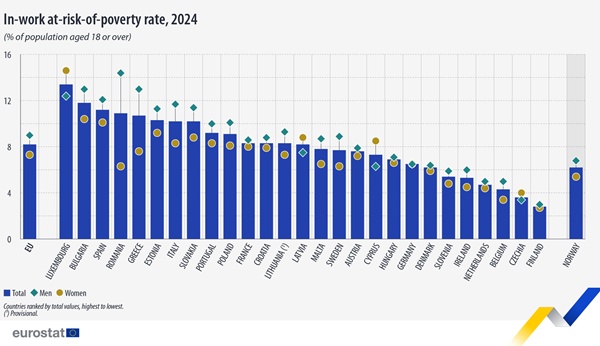

According to the latest Eurostat figures, 13.4% of people in employment in Luxembourg were at risk of poverty in 2024 - far above neighbouring countries such as Belgium (4.3%), Germany (6.5%) and France (8.3%), as well as the eurozone average of 8.2%. Nearly one-fifth of residents were at risk of poverty overall, and income inequalities remain stark: the wealthiest 20% of households enjoy a standard of living almost five times higher than the poorest 20% (sources: STATEC, CSL).

This paradox raises uncomfortable but necessary questions about Luxembourg's economic model and social cohesion.

Around 23% of households reported difficulty making ends meet in 2024 (STATEC), while 31.8% of single-parent families and 38.5% of large families were at risk of poverty (CSL). These are not abstract statistics; they reflect the daily realities of single parents struggling to cover rent or childcare costs, large families facing rising living expenses and low-skilled workers whose wages fail to keep pace with inflation and housing prices. Children are within the most vulnerable groups, alongside single-parent families, people with lower levels of education and residents of Portuguese or non-European nationality, according to STATEC.

As Chamber of Employees (CSL) President Nora Back observed in October 2025, Luxembourg's well-known prosperity "is not sufficient to mask certain persistent social gaps", with national wealth remaining "unevenly distributed" and nearly one in five residents at risk of poverty - "a reality that directly reflects the vulnerability of thousands of people to life's uncertainties."

Traditionally, employment has been viewed as one of the most reliable protections against poverty. In Luxembourg, however, this no longer seems to be the case. The risk is particularly pronounced among part-time workers: according to the CSL, part-time employment increases the at-risk-of-poverty rate by around 40%. Part-time work has also grown steadily, rising from 11% in 2000 to more than 18% in 2024. For some, this may reflect choice, but, for others, it is a necessity driven by limited full-time opportunities or family responsibilities, particularly for women.

One might expect Luxembourg's comparatively high wages to shield households from poverty. Yet, I would argue that the cost of living is disproportionately high. Housing, in particular, has become a driver of inequality. And while average gross salaries remain the highest in the EU (€83,000 in 2024), median incomes (€58,000) offer a more realistic picture of everyday living standards, with many workers earning even less.

For many households, rent or mortgage payments consume a disproportionate share of income, leaving little room for savings or unexpected expenses. STATEC figures back this up: when measured after payment of "pre-committed expenses" such as housing, the persistent at-risk-of-poverty rate rises dramatically, from 6.1% to 26.9%.

Beyond statistics, social organisations are reporting growing demand. Local non-profit organisation Stëmm vun der Strooss, once focused primarily on homelessness and addiction among vulnerable members of society, increasingly supports working families struggling to make ends meet. The rising number of children visiting its facilities with their parents is particularly alarming.

While the non-profit does not collect specific data on the working poor, staff have observed a steady rise in their numbers over the last two to three years. As a spokesperson explained, more and more people in employment are now turning to Stëmm vun der Strooss for support: "The fact that these people need to come to a place like Stëmm is one of the main reasons for the increase of beneficiaries." Indeed, the total number of people visiting the non-profit's sites rose from 2,781 in 2014 to 14,925 in 2024 (+436.7%); in 2025 the figure stood at 14,099.

These trends suggest a shift in Luxembourg's social fabric, with poverty no longer confined to the margins of society but increasingly embedded within the labour market itself.

The government argues that it has already taken decisive action. In his 2025 state of the nation address, Prime Minister Luc Frieden emphasised that reducing poverty and strengthening equity through a targeted social policy were among the coalition government's key priorities. He pointed to tax relief for low- and middle-income households, increases in the minimum wage and social benefits, extended housing subsidies and targeted support for single-parent families as evidence that the government was delivering on its promises.

In December 2025, the government also presented Luxembourg's first national action plan to prevent and combat poverty, aiming to address this multidimensional issue in a comprehensive and coordinated way.

Luxembourg prides itself on social cohesion, high-quality public services and solidarity. Yet the persistence - and, in some cases, the deepening - of in-work poverty suggests that these measures, while significant in their own right, may not be sufficient to counter the structural forces driving inequality. Perhaps it is simply too early to feel the real impact of such measures...

Yes, the government has taken steps to address poverty. However, the scale of the challenge calls for a more comprehensive, all-of-government (perhaps all-of-society) response - one that tackles not only income levels but also structural drivers such as housing, education, family policy and labour market segmentation.

In his first Christmas speech in his new position, Grand Duke Guillaume noted that even in prosperous Luxembourg, "not everyone has a roof over their head", acknowledging the impact of high living costs particularly on single parents and young people today, and calling for unity and solidarity. His words resonate because they point to a contradiction at the heart of the country's success story.

Luxembourg's challenge is no longer simply how to generate wealth, but how to ensure that economic success translates into lived security for those who sustain it. If one of Europe's richest countries cannot guarantee stability and dignity through work, perhaps prosperity itself needs to be rethought. The rise of the working poor suggests that poverty is closer to home than many of us might like to believe.